I hear my father

in a Bach sonata

the peeling of an orange

a shuffling newspaper

I hear my father

in a pounding hammer

a spinning drill

a sawblade on wood

I hear my father

in wooden shoes on gravel

the clucking chickens

dirt scraped off a spade

I hear my father

in the sizzling of oil

the cobek and ulekan (Indonesian mortar and pestle)

the skimmer in the wok

I hear my father

in a scraping chair

the pen on a school test

the slurping of coffee

I hear my father

in the splitting of firewood

the cracking of fire

content rubbing hands

I hear my father

in a plopping wine cork

a purring cat

a book being opened

I hear my father

in the laugh over a joke

said by another

or said by himself

Listen.

Tag: poetry

Oh, pickle jar

turning, twisting, trying

hard working for gherkin

If dinosaurs could talk, they'd surely swear

At comets hurtling down out of nowhere

Demise from space, turning the day to night

Rage rage, against the dying of the light

Crusty Calico Cat

Tired, Turning Twenty

Slowly Slipping, Senile

More Midnight Meowing

Brittle Bag of Bones

Gangly Greasy Geriatric

Mere Months? Maybe?

Just One More Summer.

To Lay in The Garden.

To Sleep in the Shadow.

In Smell and Shade of Tomato Plants.

To Bake on Stones, Heated in Summer Sun.

To Chatter at Birds, Many Years Younger.

Just One More Summer.

It was Heraclitus the wise

who never set foot in the same river twice

While Parmenides would have objected

that change is not to be expected.

Thus everything stayed as it was

and nothing ever came to pass.

God omnipresent - where then can I hide?

my sin and filth; my buried deeds conspire

There is no refuge, none! Not far nor wide

Deo volente, divine grace or ire

My breath constricted by this turtleneck

Head to the store, perhaps they'll take it back

The curtains in the window billow free

Sometimes I count to four, sometimes to three

My love, this fruitful garden grows for you

But would you mind if I grew roots here too?

"The speed of Nighting" My candle's flame, a call to heal the sick Many are dying, better make it quick Help dying people - it's what makes me tick

You were not meant to swim but a wave pulled you in

The frigid salt water pulled you from your slumber

How can you get back if you don't know how to swim

Sometimes you can feel it is pulling you under

This terribly tiring and terrified thrashing

drifting further out as the waves keep on crashing

attempting to stay where the sea and land meet

fighting spirit fading, resolutions recede

Submerge in the dark, and fight to draw breath

sans strength succumbing, preparing for death

engulfed by acceptance, confronting your fate

you float to the surface; the water is great!

Outside, last day of summer

Fall's first drops falling

A breeze picks up

Raincoat, my old friend.

Crown nails and a spear Swallowed down just like Jonah Get out in three days

Come join the church, beckons that kindly Pope

Reverse the Reformation, it's a cope

I cannot sola fide, got no hope

I'm shelving that Calvin

There are strange people in your house.

Helmets on their heads, bottles on their backs.

Rush in, they did. Asked if you were okay.

Walked past you, moving you aside.

Dousing things, grabbing things, moving things.

Asking what you were doing when the fire started.

Meatballs. From the fridge. Someone had

dropped them off yesterday. Kissed your cheek.

You told her she looked like your daughter.

That's a fine supper tonight, you thought.

Heat them up, on the stove. Blue gas flame

under tupperware. Smoke. Some siren started.

And now there are strange people in your house.

All future fire captains are subject to DISC

it will divine who's the leader and who is the risk

but let no one point out it's a desk horoscope

destiny in four colors, no way out, no hope.

And while you think servants can be leaders as well

even though that's not something this model can tell

We'll prophesy that you'll fail, or that you'll lose control

Because our 20 questions have shown us your all.

It's not easy to live

or to have a few breathers

when your gut's full of blood

'cause you fell 20 meters.

There is saggy skin sloshing

while I perform CPR

we both know it's pointless

and yet here we are.

Not much left of your thorax,

the structure's all gone.

Expecting cracking of ribs

yet hear the scrunch of puffed corn.

Don't give me that blank stare.

I'm trying my best!

It's been thirty minutes,

and I could use some rest.

Covered you with a sheet,

and we've cleaned up our gear.

I'm sad, tired, beat.

Hated finding you here.

I JUST WANT TO KNOW WHY.

I heard you have kids.

What went wrong in your life?

Why leave them like this?

With apologies to Wilfred Owen

The peaceful emptiness of dreams. Then -

the fire pager interrupts my sleep

where am I? Fire! Clothes! I need them -

whipped into action by the repeating beep

Bolting outside, cool morning air unnoticed

making one's way towards the engine house

by car, by bike, on foot: others approaching

the siren song is answered without pause

Helmets and suits; an ecstasy of fumbling

jump in the truck; "guys, what is the call?"

ambulance asking assistance; not unusual

we're extra hands. Likely that will be all.

Drive to the scene; too early for our sirens

still waking up, we try to find out more

"It's a hanging, boys" - suddenly it's serious

not just the extra hands we thought before

We're here; ambulance medic greets us

The captain walks ahead; he'll go and see

we must remain; anxious awaiting orders

all the while wondering: "who could it be?"

"It's one of us." No way! It can't! How could it?

Walking forward in our disbelief

Oh God. His coat, his shape, but hanging

go on! there's work to do, no time for grief

Tied to a balcony, out there facing the street

just hanging there. All stiff and cold and gone.

We must ensure the waking world won't meet

this awful sight; we'll cover under dawn.

"Don't look." Too late: his closed eyes staring

we spread out tarps, gaze burning in our backs.

Neighbours awake! And we are still preparing

work faster, now; cover the desperate tracks.

The task is done; pack up and drive the truck back.

We joke, we laugh; we mustn't show the pain

Back at the engine house, helmets and suits off

no smell of smoke. Just memories remain.

Big lumbering guy, with hands the size of shovels.

Mischievous smile, a twinkle in his eye

No signs of pain. But yet enough to kill him.

Could I have saved him, if I had known why?

In his song Ella se esconde (“She hides herself”) the Panamanian musician and politician Rubén Blades writes about a mysterious woman who has “tangled him in her mess, and has stolen his heart”.

Me has enredao en tu revulu

y me has robado el corazón!

A recurring line in his song about that woman — mystifying him yet carrying his ring around her finger — describes how she hides herself. She is his, yet hidden. She is close to his heart, yet unreachable.

Ella se esconde atras la esquina de su sonrisa.

She hides behind the corner of her smile. When you read this, an image may very well come to mind. Perhaps of a young woman, smiling yet turned away. Perhaps of just the corner of a smile, hiding everything else behind it.

In Film Theory: The Basics, film director Kevin McDonald quotes Jean Epstein‘s lyrical description of a smile as recorded in Richard Abel’s French Film Theory and Criticism,

Muscular preambles ripple beneath the skin. Shadows shift, tremble, hesitate. Something is being decided. A breeze of emotion underlines the mouth with clouds. The orography of the face vacillates. Seismic shocks begin. Capillary wrinkles try to split the fault. A wave carries them away. Crescendo. A muscle bridles. The lip is laced with tics like a theater curtain. Everything is movement, imbalance, crisis. Crack. The mouth gives way, like a ripe fruit splitting open. As if slit by a scalpel, a keyboard-like smile cuts laterally into the corner of the lips.

Richard Abel, French Film Theory and Criticism (1988)

McDonald reflects on Epstein’s work,

Epstein’s enamored tribute to the close-up of a mouth as it begins to smile redoubles film’s formal powers. His poetic language makes the object he describes strange and unusual, nearly indecipherable, but in doing so, he also foregrounds the bewitching microscopic details of human physiognomy, transforming an otherwise mundane and entirely unremarkable action into something uncanny and enchanting.

McDonald, Kevin, Film Theory: The Basics. (2022)

McDonald considers type of reflection on the close-up — something not generally used in painting, but experimented with in film — a part of photogénie, that synthesis of the technological and the aesthetic that was such a part of the early French film culture during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Bringing out a new perspective and focus through selective focus.

The smile, inviting — beckoning, perhaps — yet at times evading and obscuring. As Blades sings:

Yo me la quedo mirando.

No sé qué estará pensando,

con su cara de Mona Lisa.

I keep looking, although I do not know what she is thinking. With her Mona Lisa face.

Hiding behind the corner of her smile.

Give it a listen.

Matthew Arnold wrote his famous poem “Dover Beach” likely around the late 1840s. It has strong elements of romanticism:

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

yet this is soon followed by sadness.

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Hope, light, and sweet night air

are carried by notes of despair

And all this in a Victorian time of faith in technological progress. The Great Exhibition in Paris would open its doors in 1851, showing the world the Things To Come: Leech-using barometers (no, really — have a look), photography, pay toilets, firearms…

Ah yes, firearms. There might have been some rumblings in Europe, but weren’t there always? It wouldn’t be until 1884 before Hiram Maxim would develop the first firearm that combined the words “machine” and “gun”.

In 1882 I was in Vienna, where I met an American whom I had known in the States. He said: “Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility.”

Hiram Maxim

Arnold continues:

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

Sophocles. That playwright who makes the Antigone chorus cry:

Happy are they whose time has not tasted disaster.

Sophocles’ Antigone (excerpt) translated by Robin Bond

For a house that is shaken by gods, there the curse

fails not at all, but floods each generation in turn:

just so the swell and the surge, pushed hard by grim

blasts of storm winds from Thrace, scouring the crests

of the deep, darkling sea, stirs up the black silted sands,

beneath where the wracked and abutting cliffs resound.

Moving the poem’s theme of sea and beach along on the “turbid ebb and flow of human misery”, there follows a melancholic yearning for when the Sea of Faith was as full as that distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Arnold, though an atheist, still seems to yearn for that faith that he has found wanting and ebbing. Those “naked shingles of the world” without faith remind me of the madman’s speech which Nietzsche’s would write some years later in The Gay Science:

Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying, as through an infinite nothing?

Friedrich Nietzsche, the gay science (1882, excerpt)

Do we not feel the breath of empty space?

Has it not become colder?

Is not night continually closing in on us?

Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning?

Feeling this breath of empty space, this retreating roar of the surf on so many pebbles, the naked shingles of the world, Arnold lunges for a stronghold:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

The existential conclusion attempts to harness love as that which can move us from having to face the naked shingles of the world. Even though this world “hath really neither joy, not love, not light, not certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain”.

I can’t help but find the poem prophetic at times. Arnold writes full of romanticism, existential dread and despair during a time of great optimism in progress. Yet his ignorant armies clashing by night would eventually clash in that Great War. That same war that would have Wilfred Owen produce this other great poem, yet take his life all the same.

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Wilfred Owen, “Dulce et decorum est” (excerpt, written during WW1),

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer,

Bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Dit artikel schreef ik rond december 2022 voor de Fronteers adventkalender.

[…] als we ons afvragen wat dit wij is, wat zien is en wat ding of wereld is, komen we terecht in een labyrint van moeilijkheden en tegenstrijdigheden. Wat Sint-Augustinus zei over de tijd — dat het voor iedereen volkomen bekend is, maar dat niemand van ons het aan de anderen kan uitleggen — moet ook van de wereld worden gezegd.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Het Zichtbare en het Onzichtbare (1968)

Afgelopen herfstvakantie was ons gezin op vakantie in de Duitse Eifel. Ons zoontje Sam was 16 maanden oud, en naast rondgesjouwd worden in de schouderdrager wilde hij graag ook zelf stukjes lopen. Sam houdt niet van schoenen, en wanneer hij deze (onder luid protest) wél aan moet, gaat hij liever kruipen dan lopen. Dus dan maar op blote voeten.

Blaadjes zien

Tijdens deze wandelingen is elk gevallen herfstblaadje interessant. Voortdurend wordt het huidige opgeraapte blaadje verwisseld voor een ander blaadje dat de aandacht trekt. Sommige worden in stukjes gescheurd, andere blaadjes worden vluchtig bekeken en weer weggegooid.

Wandelingen verlopen langzaam op deze manier, maar om hem zo op zijn gemak bezig te zien met een veelvormigheid aan herfstblaadjes deed me wel afvragen: hoe ontvouwt de werkelijkheid zich voor Sam? Wat maakt juist die blaadjes interessant? Hoe ervaart hij de wereld om zich heen? En hoe heeft deze bewuste ervaring zich gevormd vanuit de “great blooming, buzzing confusion” aan indrukken waarover de psycholoog William James in 1890 schreef?

… any number of impressions, from any number of sensory sources, falling simultaneously on a mind which has not yet experienced them separately, will fuse into a single undivided object for that mind. The law is that all things fuse that can fuse, and nothing separates except what must. … The baby, assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion; and to the very end of life, our location of all things in one space is due to the fact that the original extents or bignesses of all the sensations which came to our notice at once, coalesced together into one and the same space. There is no other reason than this why ‘the hand I touch and see coincides spatially with the hand I immediately feel.’

William James, The Principles of Psychology (1890)

Ontwerpen keuren

Vanuit mijn werk in digitale toegankelijkheid word ik soms gevraagd om een ontwerp te keuren. Vaak zijn dit ontwerpen van websites, af en toe een app. Meestal binnen omgevingen zoals Figma, Invision of Adobe XD, maar ook in vroegere stadia zoals creative exploration of abstracte wireframes. De manier waarop ik naar ontwerpen probeer te kijken doet me denken aan hoe Sam misschien wel naar de wereld kijkt.

Zien

In zijn onvoltooide werk “Gedachten” — Pensées — schrijft de wiskundige, natuurkundige en filosoof Blaise Pascal over twee manieren van het benaderen van de werkelijkheid: het meetkundige denken, “l’espirit de géométrie”, en het fijne inzicht, “l’espirit de finesse”.

🇫🇷 Il y a beaucoup de différence entre l’esprit de géométrie et l’esprit de finesse. En l’un les principes sont palpables, mais éloignés de l’usage commun ; de sorte qu’on a peine à tourner la tète de ce côté-là, manque d’habitude : mais pour peu qu’on s’y tourne, on voit les principes à plein ; et il faudroit avoir tout à fait l’esprit faux pour mal raisonner sur des principes si gros qu’il est presque impossible qu’ils échappent.

🇳🇱 Verschil tussen het meetkundige denken en het fijne inzicht. Bij het eerste zijn de beginselen tastbaar, doch liggen buiten het dagelijkse leven, zodat men moeite heeft zijn hoofd in die richting te wenden omdat men dat niet gewoon is: men hoeft er slechts op te letten en men ziet de beginselen duidelijk. En men zou al helemaal een onverstandig mens moeten zijn om verkeerd te redeneren vanuit beginselen, die zo alledaags zijn dat het haast onmogelijk is eraan voorbij te zien.

Blaise Pascal, Pensées, (1669)

De geometrische geest denkt voornamelijk vanuit principes, oorzaken, gevolgen, en verbanden. Geometrisch denken maakt scheidingen tussen zaken, deelt in vakken, tekent lijnen.

De verfijnde geest denkt voornamelijk vanuit intuïtie. Het ervaren van zaken die niet per definitie duidelijk zijn voor anderen. Verfijnd denken omvat en combineert.

Bashō en Tennyson

Dit verschil tussen meetkundig en verfijnd denken wordt prachtig uitgedrukt in de manier waarop de Japanse dichter Matsuo Bashō en de Britse dichter Lord Alfred Tennyson (19e eeuw) spreken over het zien van een bloem:

🇯🇵 Yokoe mireba

Matsuo Bashō (17e eeuw)

nazoena hana sakoe

kakine kana

🇳🇱 Zie toch eens hoe

het Herderstasje bij die heg in bloei staat;

oh, kijk..!

🇬🇧 Flower in the crannied wall,

Lord Alfred Tennyson (19e eeuw)

I pluck you out of the crannies,

I hold you here,root and all, in my hand,

Little flower — but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.

🇳🇱 Bloem in de gebarsten muur,

Ik pluk je de spleten uit.

Hier houd ik je in mijn hand, wortel en al,

Klein bloemetje – kon ik maar bevatten

wat je bent, wortel en al, en al in al,

dan zou ik weten wat God en de mens is.

In beide gedichten staat het zien van — de ervaring van, de ontmoeting met — een bloem centraal. Maar de manier waarop de schrijvers een bloem ervaren verschilt sterk. Er is verwondering te lezen in beide gedichten, maar waar Bashō aanschouwt en uitnodigt, begint Tennyson met geometrie: het pakken van de bloem en daaruit te willen analyseren om uiteindelijk te willen begrijpen.

Niet zien

Beide gedichten over de bloem veronderstellen de aanwezigheid van de bloem. Dat deze is waargenomen. En hoewel ik bij het keuren van een ontwerp me probeer te realiseren wat ik zie, is het weten wat ik niet zie — en waarom — evenmin zo belangrijk. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan fenomenen zoals Banner Blindness.

Wat we waarnemen is al het product van onbewuste selecties: van alle optische zenuwsignalen die onze visuele cortex bereiken is er gewoonweg te veel om alles te verwerken. Er wordt geselecteerd op wat er voor ons relevant is, en dat wordt primair gestuurd vanuit onze doelen.

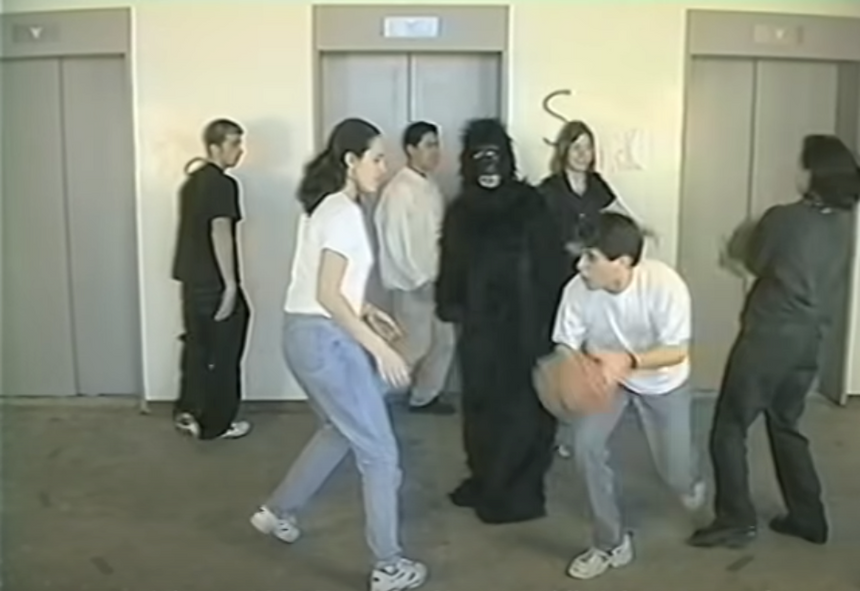

Neem het beroemde experiment waarbij er een video getoond werd waarin twee groepen mensen elkaar een basketbal toespeelden. Een groep droeg donkere t-shirts, de andere groep witte. De toeschouwers hadden een doel: ze moesten het aantal keren tellen dat de bal tussen personen met een wit t-shirt werd gepasseerd. Halverwege de video liep er een vrouw in een gorilla-pak in beeld, richtte zich naar de camera, imiteerde een gorilla door zichzelf op de borst te slaan, en liep verder. De helft van de toeschouwers bleek later de “gorilla” niet te hebben gezien.

Approximately half of observers fail to notice an ongoing and highly salient but unexpected event while they are engaged in a primary monitoring task. This extends the phenomenon of inattentional blindness by at least an order of magnitude in the duration of the event that can be missed.

Daniel Simons & Christopher Chabris, Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattention blindness for dynamic events (1999)

De selectieve perceptie binnen ons bewustzijn fungeert als een zoeklicht — de fenomenoloog Edmund Husserl noemde dit het Ichlicht, de “ik-lamp”: ons bewustzijn is altijd ergens op gericht, en daardoor zien we andere dingen niet, zoals het experiment demonstreert.

Het komt ook voor dat we meer in staat geraken om dingen waar te nemen doordat anderen dit doen. Een mooi voorbeeld hiervan is dat de ontdekking van de onverwachte planeet Uranus leidde tot meer ontdekkingen door een verschuiving van het mentaal kunnen kijken naar de werkelijkheid:

It was William Herschel’s discovery of Uranus in 1781, for example, the first discovery of a hitherto unknown planet in several millennia, that made astronomers mentally ready to notice additional ones, 67 as evidenced by the exceptionally rapid successive discoveries of the hitherto undetected four largest asteroids by three different astronomers between 1801 and 1807.

Eviatar Zerubavel, Hidden in Plain Sight (2015)

Hoe de mogelijkheid tot zien en niet-zien door cultuur en opvoeding kan worden beïnvloed, wordt ook prachtig beschreven door de taalkundige en oud-missionair Daniel Everett in het boek “Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes”. Hierin vertelt hij over zijn leven bij de Amazoniaanse Pirahã stam:

It was still around seventy-two degrees, though humid, far below the hundred-degree-plus heat of midday. I was rubbing the sleep from my eyes. I turned to Kohoi, my principal language teacher, and asked, “What’s up?” He was standing to my right, his strong, brown, lean body tensed from what he was looking at.

“Don’t you see him over there?” he asked impatiently. “Xigagai, one of the beings that lives above the clouds, is standing on the beach yelling at us, telling us he will kill us if we go to the jungle.”

“Where?” I asked. “I don’t see him.”

“Right there!” Kohoi snapped, looking intently toward the middle of the apparently empty beach.

“In the jungle behind the beach?”

“No! There on the beach. Look!” he replied with exasperation.

In the jungle with the Pirahas I regularly failed to see wildlife they saw. My inexperienced eyes just weren’t able to see as theirs did.

But this was different. Even I could tell that there was nothing on that white, sandy beach no more than one hundred yards away. And yet as certain as I was about this, the Pirahas were equally certain that there was something there. Maybe there had been something there that I just missed seeing, but they insisted that what they were seeing, Xigagaí, was still there.

Everyone continued to look toward the beach. I heard Kristene, my six-year-old daughter, at my side.

“What are they looking at, Daddy?”

“I don’t know. I can’t see anything.”

Daniel Everett, Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle (2008)

Te veel zien

De ervaring van Everett bij de Pirahā is vergelijkbaar met het probleem binnen AI en computerzicht: AI beeldherkenning is notoir slecht in het herkennen van zaken die voor de AI niet of onduidelijk bestaan. Net zoals Everett Xigagaí gewoonweg niet kan zien (en de Pirahã vergelijkbaar verkeerssignalen en markeringen niet zagen toen enkelen van hen met Everett naar een nabijgelegen stad reisden) is een AI engine niet in staat om dingen te zien die het model niet begrijpt of kent.

Dit “begrip van de wereld” probleem is onderdeel van het Frame Problem. De cognitief wetenschapper en filosoof Daniel Dennett schrijft over de opgave om een AI systeem te bouwen wat op elk moment uit de werkelijkheid die het ervaart de juiste patronen weet te herkennen, en conclusies te trekken zonder in eindeloze verwerking terecht te komen waarbij de juiste aannames over de wereld worden gebruikt. Dennett beschrijft op humoristische wijze hoe een voor mensen relatief eenvoudige taak als een boterham smeren voor een AI een onoverkomelijk moeilijk probleem kan zijn. Hoe weet de AI (met zogenaamde AGI – “algemene intelligentie”) dat het temperatuurverschil in de kamer waar het zich bevindt niet relevant is voor de opdracht die het moet uitvoeren — of het feit dat er op dat moment geen olifanten in de buurt zijn? Een model als GPT-3 is tot indrukwekkende resultaten in staat, maar handelt exclusief binnen het gebied van taalkundige verwerking en valt daardoor onder narrow AI.

What is needed is a system that genuinely ignores most of what it knows, and operates with a well-chosen portion of its knowledge at any moment. Well-chosen, but not chosen by exhaustive consideration. How, though, can you give a system rules for ignoring – or better, since explicit rule-following is not the problem, how can you design a system that reliably ignores what it ought to ignore under a wide variety of different circumstances in a complex action environment?

Daniel Dennett, Cognitive Wheels: The Frame Problem of AI (1984)

En hoewel wij mensen er in vergelijking met AI vreselijk goed in zijn om de complexe werkelijkheid tot de voor ons relevante patronen terug te brengen — iets dat we ons zelden beseffen — probeer ik me er bij het keuren van een ontwerp van bewust te zijn dat ik in patronen en heuristiek naar een ontwerp kijk, en dat dit voor anderen kan verschillen. Ik probeer te schakelen in de manier waarop ik naar het ontwerp kijk, en me voor te stellen hoe dit voor anderen en hun context en doelen zou kunnen zijn. Ik probeer te schakelen tussen manieren van waarnemen, á la Pascal.

Anders zien

Als ik naar de Grand Canyon kijk, kan ik dit op meerdere manieren zien. Als enorm ravijn, als scheur in een landschap, en als doorsnede van een vreselijk oude planeet.

Als toeristen-attractie. Als geologisch fenomeen. En ga zo maar door.

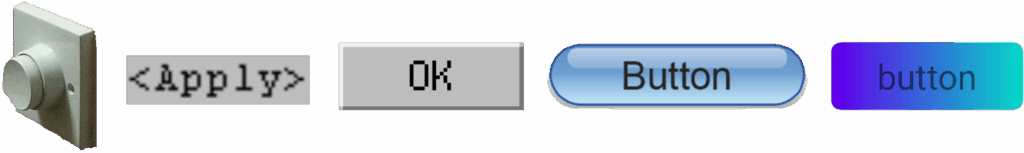

Wanneer ik zo actief aan het perception-switchen ben merk ik dat het me helpt om een ontwerp anders te zien, en me beter voor te stellen hoe een gedeelte verkeerd begrepen zou kunnen worden, of onduidelijk is. Ik probeer dingen terug te brengen tot hun essentie, tot datgene wat ze maakt dat ze zijn. Van knop, tot navigatiebalk, tot blogpost.

Wat maakt bijvoorbeeld dat een knop een knop is? Dat is geen eenvoudige vraag. Om Pascal er weer bij te halen: je kunt een vraag als deze beantwoorden via het meetkundige denken — de plaats, contrast, tekst, grootte — maar ook met de verfijnde geest: waarom vind ik dit een knop?

First and foremost, buttons should easily bend to the will of their operators; they should cause no difficulty for pressers …

Hart & Hegeman Manufactoring Corporation, Push Switch (1905)

Maar vergeet het experiment met de gorilla niet: we bekijken, filteren en verwerken de werkelijkheid afhankelijk van onze doelen. Dus ook: verwacht ik daar een knop?

Een “plek om van af te vallen” en een “plek om van af te stappen”

In zijn boek “The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception” schrijft psycholoog James Gibson (bekend van het begrip affordance, hoewel deze term is terug te voeren naar Kurt Lewin’s “Aufforderungscharakter”) onder andere over hoe wezens de omgeving om hen heen waarnemen:

A brink, the edge of a cliff, is a very significant terrain feature. It is a falling-off place. It affords injury and therefore needs to be perceived by a pedestrian animal. The edge is dangerous, but the near surface is safe. Thus, there is a principle for the control of locomotion that involves what I will call the edge of danger and a gradient of danger, that is, the closer to the brink the greater the danger. This principle is very general.

A step, or stepping-off place, differs from a brink in size, relative to the size of the animal. It thus affords pedestrian locomotion. A stairway, a layout of adjacent steps, affords both descent and ascent. Note that a stairway consists of convex edges and concave corners alternating, in the nomenclature here employed.

James Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (1979)

Deze manier van de omgeving waarnemen — als iets dat faciliteert: af-vallen, of af-stappen — probeer ik ook toe te passen op de manier waarop ik naar een ontwerp of een interface kijk. Dat betekent concreet dat ik probeer te zien wat het element van de interface betekent voor mij als gebruiker.

Dus niet alleen sign-up-formulier, maar ook uitnodiging om lid te worden, en plek om informatie te delen. Niet alleen link, ook navigatie, verplaatsing, en in het geval van bijvoorbeeld een link “view comments” ook interpretaties als “plek met bijdragen”, waaruit wellicht de vraag komt of het relevant is dat de hoeveelheid comments er bij wordt vermeld, en waarom er comments mogelijk zijn, hoe dat past in de rest van de interface, en zo verder.

Deze “reducerende geest” die voortdurend de vraag stelt “waar kijk ik naar, en welke ervaring heb ik hierbij?” is terug te vinden in de kunsten. Zie bijvoorbeeld hoe een tronie zoals het Meisje met de Parel een grotere gelijkenis vertoont met de zintuigelijke ervaring, terwijl het kubisme van Picasso experimenteert met herkenbaarheid, vormen en patronen. De Black Square van Malevich en Composition II in Red, Blue and Yellow van Mondriaan stellen ons steeds weer de vraag over wat het is om naar pure vormen, lijnen en kleuren te kijken en wat dit met ons doet.

Een iconische meubel zoals de Zig-Zag Stoel van Rietveld doet dit vergelijkbaar. We zien waarschijnlijk dat het een stoel is. Maar waarom? Wanneer is dit niet langer het geval? Voor wie is dit geen herkenbare, of zelfs bruikbare stoel?

Dit raakt aan zowel ontologie — de categorieën van het Zijn — als aan fenomenologie: wat is het om te ervaren? Welke categorieën en beelden komen in ons op wanneer we kijken, wanneer we lezen?

Merels zien

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.O thin men of Haddam,

Wallace Stevens, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird [stanzas I, II, VII] (1954)

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

Goede kans dat tijdens het lezen van deze 3 stanza’s er allerlei beelden door je hoofd schoten. Van bergen, vogels, bomen en meer. Hoe zagen die bomen er uit?

Binnen de cognitieve psychologie wordt een mentale categorie (zoals “vogel”) een concept genoemd. In het geval dat je je een voorstelling maakt van een voorbeeld binnen de categorie heet dit een prototype. Deze worden beïnvloed door je ervaringen: binnen de categorie “vogel” zul je eerder aan een kraai, roodborstje, meeuw of adelaar denken dan aan een pinguïn.

Binnen de fenomenologie is dit vergelijkbaar met de essentie van een ding: de fundamentele manier waarop het in je bewustzijn bestaat. Wanneer je bijvoorbeeld over een boom nadenkt, heeft die boom in je bewustzijn meerdere dimensies. Een voorkant, een achterkant. Ook al is de fysieke boom waar je naar kijkt op dat moment voor jou alleen van 1 kant te bekijken.

En ook al mocht je niet naar een daadwerkelijke boom kijken — misschien is het wel een als boom verklede front-end ontwikkelaar — in je bewustzijn is de essentie van het ding nog steeds een boom.

Dit alles geldt ook voor een knop. Een navigatiebalk. Een invoerformulier. Wanneer je aan een “OK knop” denkt, heb je daar een bepaald beeld en verwachting bij. Bij het doelmatig verkennen van een ontwerp filter je daar op. Zoals je op zoek gaat naar dat éne stukje Lego. Zo probeer ik me bij het keuren van een ontwerp ook nadrukkelijk bewust te zijn van de onbewuste verwachtingspatronen die ik hanteer. Paradoxaal als dat klinkt.

De aspecten van de dingen die voor ons het meest belangrijk zijn blijven ons door hun eenvoud en alledaagsheid verborgen. (Je merkt het niet op — omdat je het altijd voor ogen hebt.) De echte grondbeginselen van ons onderzoek vallen ons niet op.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Filosofische Onderzoekingen (1953) (geparafraseerd)

Symbolen zien

Tijdens het kijken naar een ontwerp komen er veelvuldig symbolen en iconen voorbij. Ik probeer me hierbij bewust te zijn van de cultuursemiotiek — waarom ik bepaalde symbolen kan interpreteren — en tot in hoeverre de symbolen kunnen bijdragen aan de begrijpbaarheid van het ontwerp. En hoewel het ▶️ ”play” symbool binnen de context van een video bijna universeel begrepen wordt, geef ik er nog steeds de voorkeur aan om er tekst bij te plaatsen. Andersom kunnen symbolen de begrijpbaarheid van tekst vergroten:

Today, people are more visually wired. They follow directions with text and graphics 323% better than with text alone. Images are also more persuasive. … In electronic contexts—including computer screens, the World Wide Web, multimedia environments, and virtual reality—the use of visual icons can be compared to written language because visual icons execute computer commands […] understanding the relationship between iconic desktops and physical ones is a key concept behind user-friendly metaphors.

Susan B. Barnes: An Introduction to Visual Communication: From Cave Art to Second Life (2nd edition) (2011) – mijn nadruk.

The argument that we should consider the combination of text and icon as a solution to our communicative objective may be a positive step forward. Is it not true that we see in our everyday life people combining spoken language with gestures, hand and eye movements, intonational variations?

Masoud Yazdani, Iconic Communication [chapter 6: Communication Through Icons, by Philip Barker and Paul van Schaik] (2000)

Kom en zie

Uiteindelijk beschouw ik het keuren van een ontwerp als een existentiële handeling. Het vertelt me iets over een ander, of anderen: zij die het ontwerp tot stand brachten. Het zegt iets over hun kijk op de wereld, en hoe een spectrum van mogelijke doelen door hen naar een ontwerp wordt vertaald.

Tegelijkertijd vertelt het me ook over mijzelf: de dingen die ik zie (of niet zie) bij het ervaren van het ontwerp. Het schrijven van het rapport dwingt me om deze ervaring — en de daaruit voortvloeiende observaties — in concrete taal op te schrijven. Om na te denken over datgene waar ik precies naar kijk en hoe ik tot die conclusie kom.

Zo gezien (sorry) is ontwerp-keuring een voortdurende dialoog op meerdere aspecten. Een dialoog met een toekomstig gebruiksscenario: wat kan hier misgaan? En op welke manieren en waardoor? Welke perspectieven kan ik hanteren om het ontwerp anders te zien? Van welke dingen ben ik me misschien minder of niet bewust?

One sees the environment not with the eyes but with the eyes-in-the-head-on-the-body-resting-on-the-ground.

James Gibson

Wat we zien, en niet zien. De herfst, het bos, het asfaltpad. Je vrouw. Je zoontje. Blote voetjes. Een vuistje met herfstblaadje.

Met dank aan Dick Verstegen. Alle afbeeldingen via Wikipedia behalve wanneer anders vermeld.